Kristallnacht

On the night of November 9–10, 1938, Nazi German leaders unleashed a nationwide anti-Jewish riot. The violence was supposed to look like an unplanned outburst of popular anger against Jews. In reality, this was state-sponsored vandalism, arson, and terror. This event came to be called Kristallnacht (Night of Broken Glass). It is also referred to as the November Pogrom.

Key Facts

-

1

During Kristallnacht, Nazis burned more than 1,400 synagogues, vandalized thousands of Jewish-owned businesses, broke into Jewish people’s apartments and homes, and desecrated Jewish religious objects. They also humiliated, assaulted, and killed Jewish people.

-

2

As part of Kristallnacht, the German police imprisoned about 26,000 Jewish men in concentration camps just because they were Jewish.

-

3

In the aftermath of Kristallnacht, the Nazi regime ordered the Jewish community to pay a 1 billion Reichsmark “atonement payment.” The regime also rapidly enacted many anti-Jewish laws and decrees.

Kristallnacht was a nationwide, violent anti-Jewish riot that took place throughout Nazi Germany on November 9 and 10, 1938. During Kristallnacht, groups of Nazis and other Germans targeted Jewish places of worship, stores and businesses, homes, and people. The perpetrators included Nazi Party officials and members of Nazi Party organizations, especially the SA, SS, and Hitler Youth. German civilians unaffiliated with these Nazi organizations also participated. Many took the opportunity to steal items from vandalized Jewish homes and businesses, and to publicly humiliate their Jewish neighbors.

Top Nazi leaders coordinated and instigated the Kristallnacht riot. However, they intended for it to look like an unplanned outburst of popular anger against Jews. They portrayed the violence as a spontaneous response to a Jewish teenager’s assassination of a minor German diplomat. But the violence was not spontaneous. Nazi officials used the incident as an excuse to launch the riot.

Kristallnacht was state-sponsored vandalism and arson. Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels and other top Nazis actively coordinated the riot with the support of Nazi leader Adolf Hitler.

Why is it called “Kristallnacht”?

The nationwide anti-Jewish riot of November 1938 is known by many names.

In November 1938, Nazi German authorities typically referred to the events as an Aktion (meaning “operation” or “action”). Sometimes they called it the “Jewish action” or the “revenge action.”

Jewish people and groups often referred to the events as a pogrom. The word pogrom comes from Russian and had been used since the 19th century to describe mass violence against Jews in the Russian Empire and beyond. By using this term, Jewish observers placed the event in a longer history of antisemitism and anti-Jewish violence. The word “pogrom” also frequently appeared in American press coverage of Kristallnacht.

Eventually, the term Reichskristallnacht came into popular usage among the German public during the Nazi era. The word means “Reich Night of Crystal.” It was a reference to shards of shattered window glass that lined German streets. “Reichskristallnacht” was eventually shortened to “Kristallnacht.” In English, Kristallnacht is often translated as “Night of Broken Glass.”

Today, the events of Kristallnacht are commonly referred to in German as the Reichspogromnacht (Reich pogrom night) or the Novemberpogrom (November Pogrom).

Prelude to Kristallnacht

The year 1938—the year that Kristallnacht occurred—was a turning point in Nazi Germany. That year, Nazi Germany began to more aggressively pursue its ideological goals. It expanded its territory by annexing Austria in March and the Sudetenland in September–October.

Throughout 1938, the Nazi regime also carried out increasingly restrictive and violent anti-Jewish measures. Their goal was to drive Jews out of Nazi Germany. In this context, the Nazi regime targeted Jews with Polish citizenship and passports living in Germany and its annexed territories. On October 27–29, 1938, German authorities rounded up and deported more than 17,000 Jewish people, many of whom had been born in Germany. This measure, often called the Polenaktion (Polish Action), was the first mass deportation of Jews from Nazi Germany.

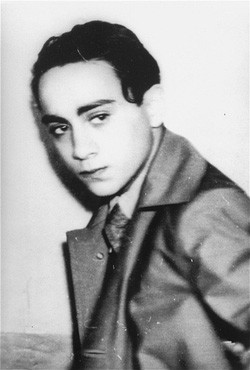

Among those whom the Nazi German authorities deported was the Grynszpan family. Zyndel and Ryfka Grynszpan (who had immigrated to Germany in 1911) were deported from Hanover to Zbąszyń in Poland, along with two of their children. Their 17-year-old son Herschel was living in Paris at the time. After learning about his family's deportation, Herschel went to the German Embassy in Paris. There, on the morning of November 7, he shot minor German diplomat Ernst vom Rath, mortally wounding him. Grynszpan likely acted out of anger over the deportation from Germany of his parents, siblings, and other Jews with Polish citizenship.

The Nazi regime chose to use the shooting as an excuse to launch an anti-Jewish riot. Beginning on November 7, Propaganda Minister Goebbels coordinated the German press response to the shooting of Rath. Nazi newspapers publicized the attack. They incited anti-Jewish violence by blaming the shooting on all Jews. The Nazi regime claimed that Grynszpan was part of a world Jewish conspiracy. In some places, local Nazis took matters into their own hands, attacking synagogues and Jewish-owned businesses.

Inciting Kristallnacht: The Night of Wednesday, November 9, 1938

Nazi anger over the shooting of Rath came to a head on the evening of November 9.

5:30 p.m., November 9, 1938: Rath’s Death

On November 9, Nazi Party leaders from across Germany gathered in Munich for the annual commemoration of the Beer Hall Putsch, Hitler’s failed attempt to seize power in Germany in 1923. That evening, Hitler and other Nazi leaders learned that Ernst vom Rath had died from his wounds. From that moment, the events of Kristallnacht unfolded quickly.

9:30–10:00 p.m., November 9, 1938: Goebbels’ Speech

Following the news of Rath’s death, Hitler and Goebbels decided to instigate a nationwide anti-Jewish riot. Around 9:30 or 10 p.m., Goebbels delivered a passionate antisemitic speech to Nazi dignitaries gathered in Munich. After the speech, Nazi officials telephoned their home districts and shared Goebbels’ instructions with their subordinates.

11:55 p.m., November 9, 1938: Gestapo Orders

Heinrich Müller, Chief of the Gestapo, issued an internal notice of a large-scale action against Jews. He ordered the arrest of 20,000–30,000 Jewish men. He instructed the police to focus on detaining “wealthy Jews.”

1:20 a.m., November 10, 1938: Heydrich’s Instructions to Police

At 1:20 a.m., Chief of the Security Police and SD Reinhard Heydrich sent more detailed orders to German police forces. He ordered the police not to interfere with what he called “demonstrations.” Instead, he instructed them to:

- ensure that the riots did not threaten non-Jewish lives or property;

- guarantee that rioters did not steal any items from Jewish-owned homes and stores targeted with vandalism;

- remove all synagogue archives and transfer them to the Security Service (Sicherheitsdienst, or SD); and

- arrest young, healthy, affluent Jewish men.

Heydrich’s order meant that the police were instructed to allow crimes—including vandalism and arson—to happen without intervening.

Kristallnacht: The Violence on November 9–10

Late on the night of November 9, instructions for the riot spread from Nazi leaders in Munich to other parts of Germany and its annexed territories. In the middle of the night and into the next day, groups of Nazis affiliated with the SA, SS, and Hitler Youth began the assault. In small towns and major cities, they rampaged through their communities. Sometimes they wore their Nazi uniforms. At other times, they appeared in civilian clothes. Ordinary German civilians often chose to join in the riot. The perpetrators and victims frequently knew each other, especially in small towns and villages.

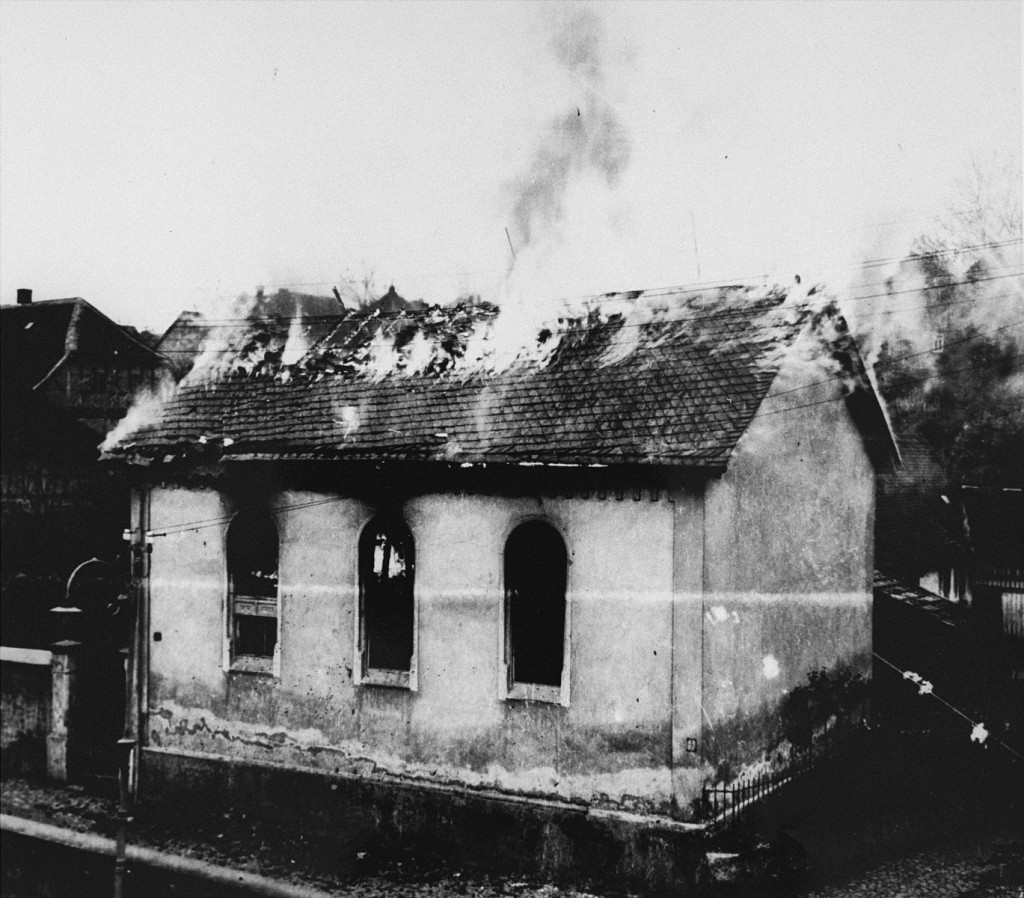

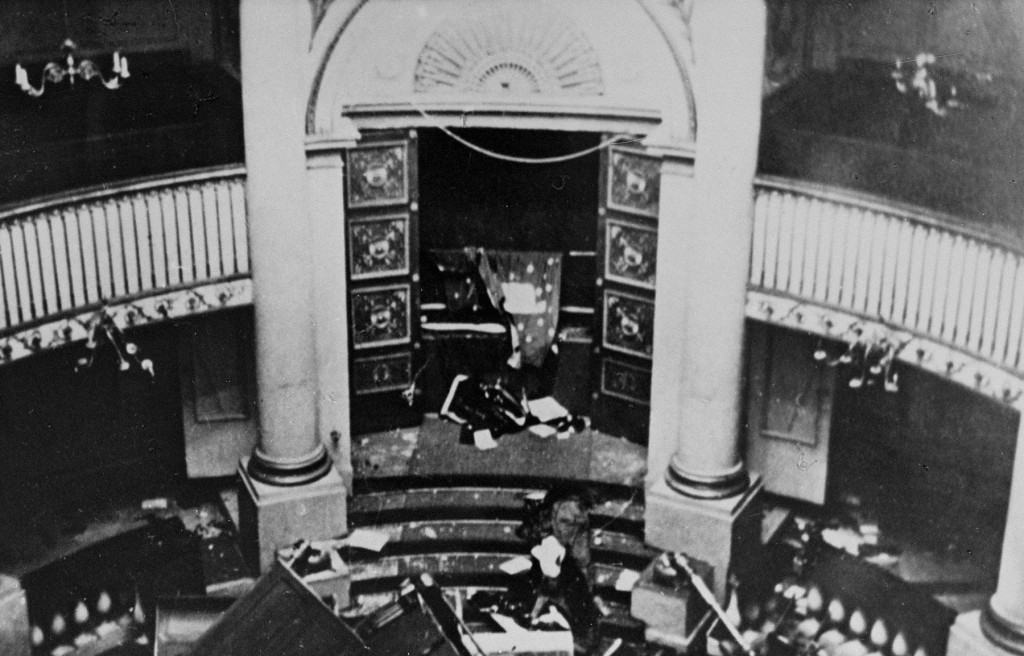

Burning Synagogues

During Kristallnacht, groups of Nazis destroyed more than 1,400 synagogues throughout Germany and its annexed territories. They also destroyed other Jewish religious and communal buildings, including prayer houses in Jewish cemeteries. In most cases, local Nazis set fire to the synagogues. Sometimes they used explosives to destroy the buildings. Local firefighters stood by. They had received orders only to prevent flames from spreading to nearby buildings.

Germany’s synagogues burned throughout the night and the next day in full view of the public. In many cases, the burning synagogue became a public spectacle, with crowds of onlookers. In some locales, Jews were forced to clean up the debris.

In multiple towns, German schoolchildren were brought to watch and join in the public spectacle.

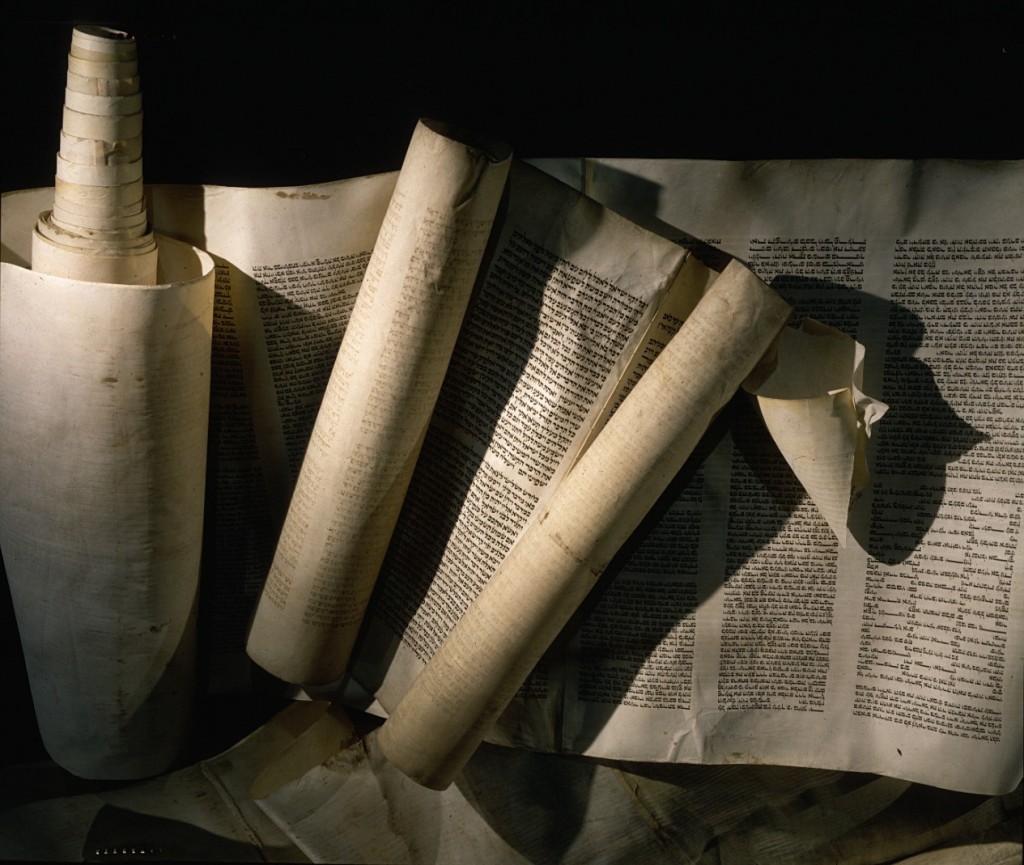

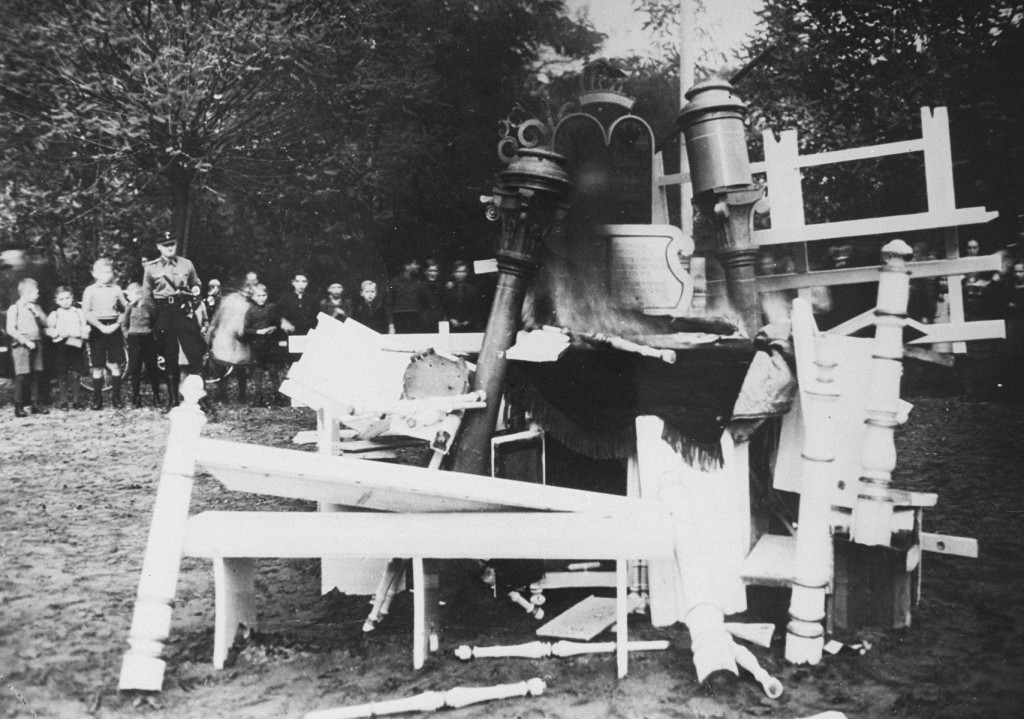

Desecrating the Torah

As part of the wanton destruction of Jewish houses of worship, Nazis also desecrated religious texts and other sacred Jewish objects and clothing, such as prayer shawls. Throughout Germany and the annexed territories, groups of Nazis destroyed holy Torah scrolls by throwing them onto the ground, tearing them, burning them, or tossing them into rivers.

In some cases, the perpetrators forced the local rabbi and other members of the Jewish community to watch, or even participate, in these sacrilegious actions.

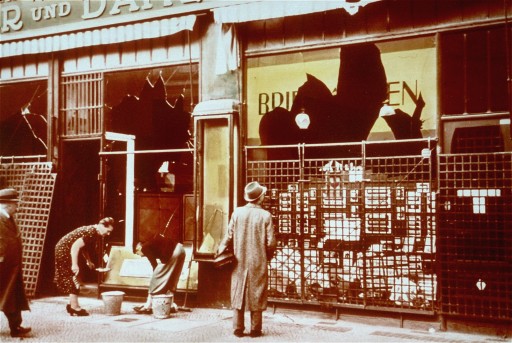

Vandalizing Jewish-Owned Businesses

Across Germany and its annexed territories, groups of Nazis vandalized thousands of Jewish-owned stores and businesses. They shattered the glass storefront windows, destroyed shop wares, and painted graffiti. Even though the regime had instructed people not to loot, theft was common. This was a culmination of almost five years of Nazi propaganda, boycotts, and threats.

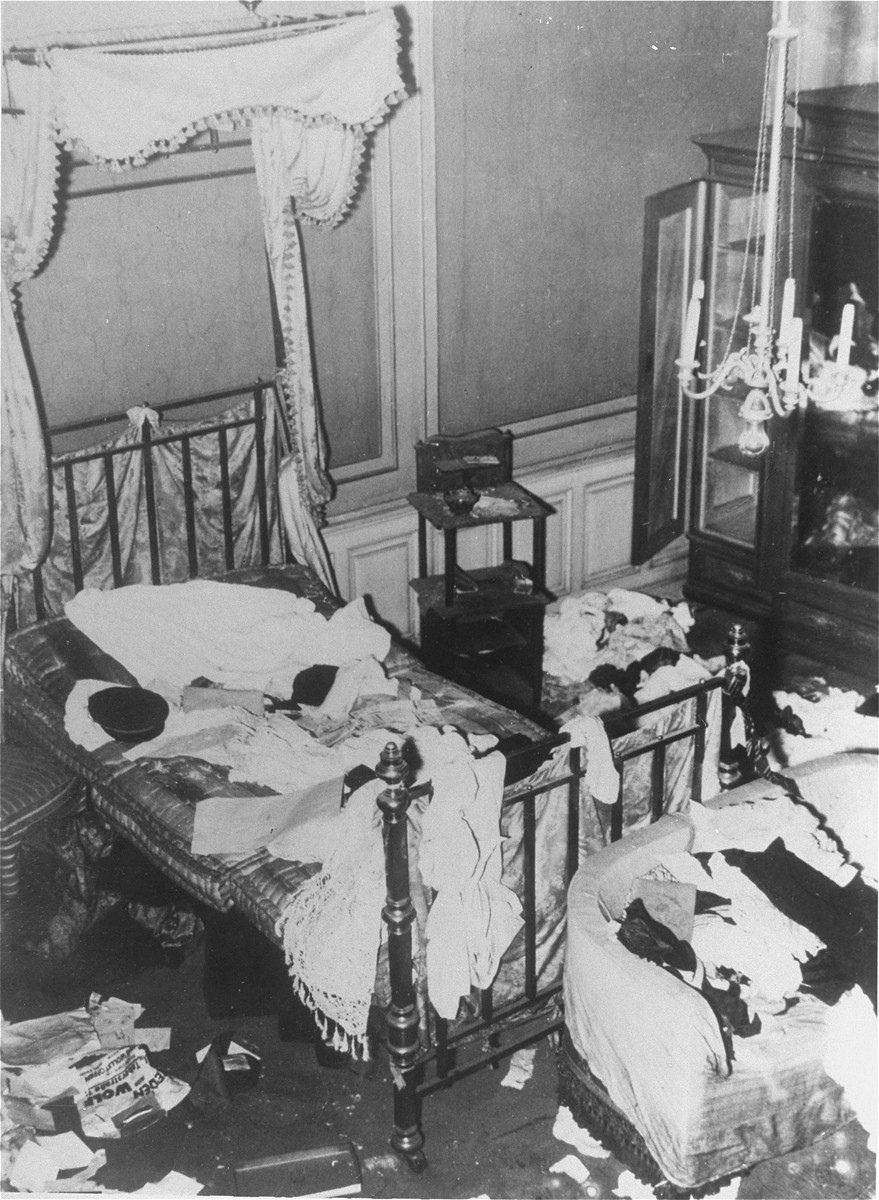

Breaking into and Vandalizing Jewish Residences

Groups of armed Nazis broke into and vandalized thousands of Jewish people’s homes, terrorizing the residents. In some cases, they beat down the doors to gain entry. Perpetrators threw rocks and bricks into Jewish people’s windows. This often took place in the middle of the night, with Jewish people dragged from their beds.

The rioters threw people’s furniture out of windows and smashed their dishes, glassware, windows, and mirrors. They ripped the pages of their books. The vandals ruined Jewish families’ linens, clocks, toys, artwork, musical instruments, clothing, and other personal items. The perpetrators used sledgehammers and axes to smash things. They cut open blankets and pillows with knives, covering homes and streets in feathers. They used water and ink to destroy other items. In many cases, perpetrators stole valuable belongings from Jewish people. In some cities, Nazi mobs even attacked Jewish orphanages, old-age homes, and hospitals.

The violent assault on Jewish people’s homes was a shocking violation to the victims. Previously, most anti-Jewish measures had been public, related to work and businesses. Kristallnacht shattered the illusion that, for Jews, home could be a sanctuary from public ostracism and danger.

Publicly Humiliating and Tormenting Jews

Nazis also publicly humiliated and taunted Jewish people during Kristallnacht. They forced them to do demeaning tasks. These tasks varied from town to town, but included forcing Jews to: perform calisthenics and other exercises, regardless of their age or health; crawl and bark like dogs; dance in celebration of the destruction; sing Nazi songs; and read aloud from Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf.

Crowds of Germans participated in the humiliation. They spat on, taunted, and threw mud at their Jewish neighbors. The victims were often still clothed in their pajamas.

Assaulting and Killing Jewish People

During Kristallnacht, mobs of Nazis violently assaulted and even killed Jewish people. As they invaded people’s homes, groups of Nazis often beat and physically abused Jews. There are documented cases of individuals sexually assaulting, shooting, and stabbing Jews on November 9–10.

Hundreds of Jewish people died during Kristallnacht and its aftermath. Some were deliberately killed during the riot. Others were shot, stabbed, or beaten so severely that they later died from their wounds. Additionally, Jewish people died due to medical events, such as heart attacks, resulting from the shock of the riot. During and in the aftermath of Kristallnacht, hundreds of Jewish people died by suicide.

Arresting and Imprisoning Jewish Men in Concentration Camps

During Kristallnacht, the police arrested tens of thousands of Jewish men on orders from top Nazi officials. This was the first instance in which the Nazi regime incarcerated Jews on a mass scale simply because they were Jewish. These arrests terrorized the Jewish community.

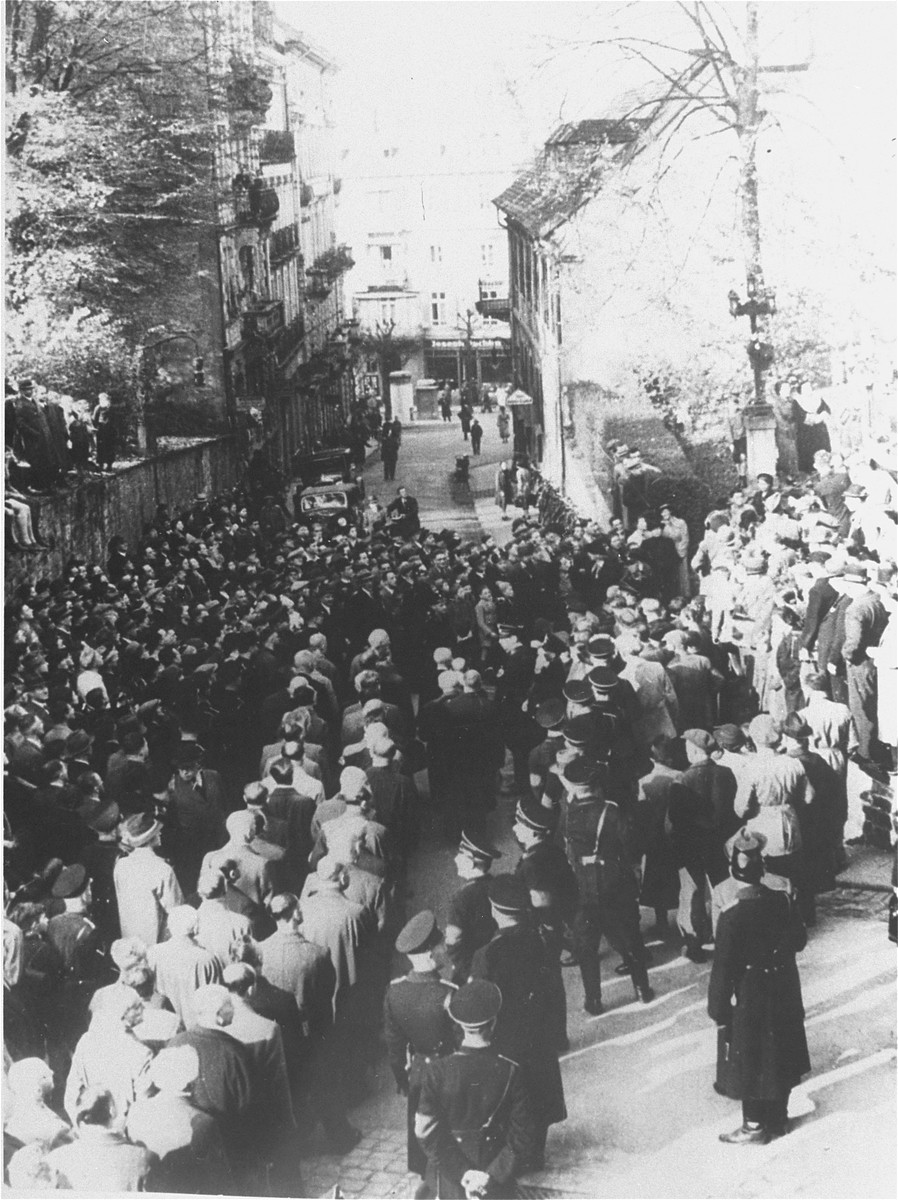

In accordance with the orders issued by Müller and Heydrich, the German police began to carry out the arrests in the early morning hours of November 10. SS and SA men assisted the German police, often detaining and abusing Jewish men. Typically, the arrested men were detained in a local prison, police station, or large holding place. In many cases, the authorities marched the arrested men through public streets in full view of the local community.

Some of the arrested men were released, but most were transferred to the Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen concentration camps. In total, about 26,000 Jewish men were imprisoned in the three camps. The camp system was not adequately prepared for so many prisoners. The Jewish men were housed in primitive, overcrowded, and unsanitary conditions. In the camps, the SS guards treated the Jewish men with cruelty and brutality, regularly yelling at and beating them. Hundreds died as a result of the brutal treatment they endured.

Most of the Jewish men were released after several weeks. In some cases, they had to sign over their businesses or prove they had plans to emigrate. Their wives, mothers, and other family members often bravely confronted the Nazi regime to help secure their freedom.

The Nazi Regime and the Aftermath of Kristallnacht

The Kristallnacht riot lasted for about 24 hours. As the violence came to an end, the Nazi regime began to deal with the economic, legal, and public fallout. Although the regime had coordinated the riot, Nazi leaders had not planned it carefully. Exactly how they would handle the consequences was a matter of improvisation.

Calling off the Violence

At 4 p.m. on November 10, 1938, the Nazi regime called off the riot.

Joseph Goebbels issued a statement broadcast over the radio stating in part: “A strict order is now being issued to the entire population to desist from all further demonstrations and actions against Jewry…The definitive response to the Jewish assassination in Paris will be delivered to Jewry via the route of legislation and edicts.”

The statement ran on the front pages of newspapers the following day. Internally, various Nazi Party leaders also tried to call off the riot. Even with these orders, mob violence continued into at least the next day.

Contending with Public Opinion at Home

The widespread destruction of Kristallnacht shocked many people, including members of the German public who had witnessed the violence and its aftermath firsthand. While many Germans had enthusiastically participated in the riot and publicly humiliated their Jewish neighbors, many other Germans had not. A few intervened to help. Some expressed solidarity with their Jewish neighbors or criticized the perpetrators. The wanton destruction of valuable property was especially unpopular. Some Germans condemned the attacks on synagogues because they were attacks on houses of worship. There were even some objections from Christian leaders.

Hoping to shape public opinion in the Nazis’ favor, Goebbels instructed the Nazi press to downplay the severity of the Kristallnacht events. Nazi propaganda continued to viciously attack Jews and demonize Herschel Grynszpan, while also emphasizing that an anti-Jewish riot would not happen again.

Forcing Jews to Pay for the Property Damage

The Nazi regime also had to deal with the economic consequences of the riot. Some Nazi leaders, especially Hermann Göring, feared that the extent of property damage was so large that it would harm the German economy. On November 12, Göring led a meeting of top Nazi leaders, where he announced orders from Hitler. These included:

- Jews would be required to pay a fine of one billion Reichsmarks as an “atonement payment” for “Jewry’s hostile attitude toward the German people and Reich”;

- Jewish owners would be held responsible for paying for and repairing the damage caused by the rioters; and

- Jews could not collect insurance payments for their damaged property. Instead, the payments would be confiscated by the German government.

Combined, these measures forced Jews in Germany to pay the Nazi German regime for assaulting and attacking them. This further impoverished Germany’s Jews.

Facing the Legal Consequences

Most of what rioters did on the night of November 9–10 was against the law. In Germany, it was illegal to set fire to buildings, break into people’s houses, and vandalize stores. However, the police had been instructed not to intervene. In almost all cases, they followed this command.

On November 19, the Ministry of Justice sent secret instructions to German prosecutors, informing them how to proceed with cases related to the events of November 9–11. Prosecutors were told not to pursue cases of property damage to synagogues, Jewish-owned shops, or Jewish residences. However, they were instructed to prosecute plunder, homicide, and crimes committed against Aryans. The Gestapo was responsible for conducting the initial investigations, and most cases were dismissed. In the end, the Nazi regime did punish some individuals for certain crimes, including sexual assault. Most of the perpetrators, however, received light sentences.

Anti-Jewish Laws and Regulations after Kristallnacht

In the month following Kristallnacht, the Nazi regime enacted a series of laws and decrees targeting Jews. Among other things, these measures banned Jews from carrying firearms, operating retail stores, receiving most forms of public welfare, and attending public school. On November 28, a German government decree permitted state and local officials to impose restrictions on when and where Jews were allowed to appear in public. This set the legal groundwork for curfews and other measures restricting Jews’ movements. Finally, a decree on December 3, 1938, regulated the takeover of Jewish-owned businesses and property. This process, which amounted to widespread theft, was called “Aryanization.”

Combined, these laws and decrees almost completely removed Jews from German economic and social life. They signaled a serious escalation in the Nazis’ anti-Jewish policies. The goal was to use any means available to force Jews to leave Nazi Germany and to confiscate as much of their property and wealth as possible.

International Reactions to Kristallnacht

Across Europe and North America, the events of November 1938 received significant press coverage. In the United States, newspapers covered the riots extensively. US President Franklin D. Roosevelt denounced Nazi Germany’s attack on Jews. The president also called the US ambassador to Germany, Hugh Wilson, back to the United States for consultation. In Great Britain, the government allowed aid groups to organize Kindertransports, which ultimately helped thousands of children escape Nazi control.

Why is Kristallnacht important?

Kristallnacht was a watershed. At the time, observers commonly referred to it as savagery or barbarism. Many insisted that it violated the basic rules of civilization and progress.

The specific violent actions were not unprecedented: vandalism and assault had been Nazi anti-Jewish tactics for years. But, Kristallnacht was shocking—that night, assault, robbery, vandalism, and arson happened all at once, in a short period of time, all across Germany and its annexed territories. These were not isolated acts of violence, but systemic state-sponsored terror.

Kristallnacht sent a clear message: Jews were not welcome in Germany. Targeting Jewish-owned stores and businesses further drove Jews out of German economic life. The burning of Jewish houses of worship erased the most visible form of Jewish life from Germany’s cityscapes. Invading Jewish people’s homes and destroying their private and most intimate possessions demonstrated that nowhere in Germany should be considered safe for Jews. The arrests of innocent Jewish men without cause showed how far the Nazi regime was willing to go to drive Jews out of Germany.

Jews heard the message loud and clear. After Kristallnacht, many decided that there was no future for them in Germany.

Footnotes

-

Footnote reference1.

The majority of the deportees were long-term, legal residents of Germany. A significant number had been born in Germany. The latter did not have German citizenship because German citizenship law was based on the parents’ citizenship status, not on the individual’s place of birth.

Critical Thinking Questions

How did the events of Kristallnacht compare to previous anti-Jewish actions and violence in Germany under the Nazis?

Consider the range of reactions to the violence of Kristallnacht among the German people. What pressures and motivations may have influenced their choice to participate, to help the victims, or to turn away?

How did the United States and other nations respond to the news of Kristallnacht? What factors might have influenced their responses?

Kristallnacht was an example of targeted violence against a minority group. How can understanding its impact help individuals recognize and respond to signs that a country is at risk for genocide or mass atrocities?